The 2019 edition of Art Basel Miami Beach seems to have been all about one work: Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan — an installation consisting of a banana duct-taped to a wall, which went on to be sold for a price of $120,000, which was then peeled off the wall and eaten by a ‘hungry’ performance artist. And as I write this, the replacement piece has been taken off the wall altogether because of crowd management issues and in view of the safety of other works around.

While the world still keeps going bananas over this banana (No love for the duct tape? Anyone?), let’s take a step back and look at the questions it has raised — and why a humble fruit taped to a wall might be one of the most important things to have happened to the art world in recent years.

But first, a short history lesson…

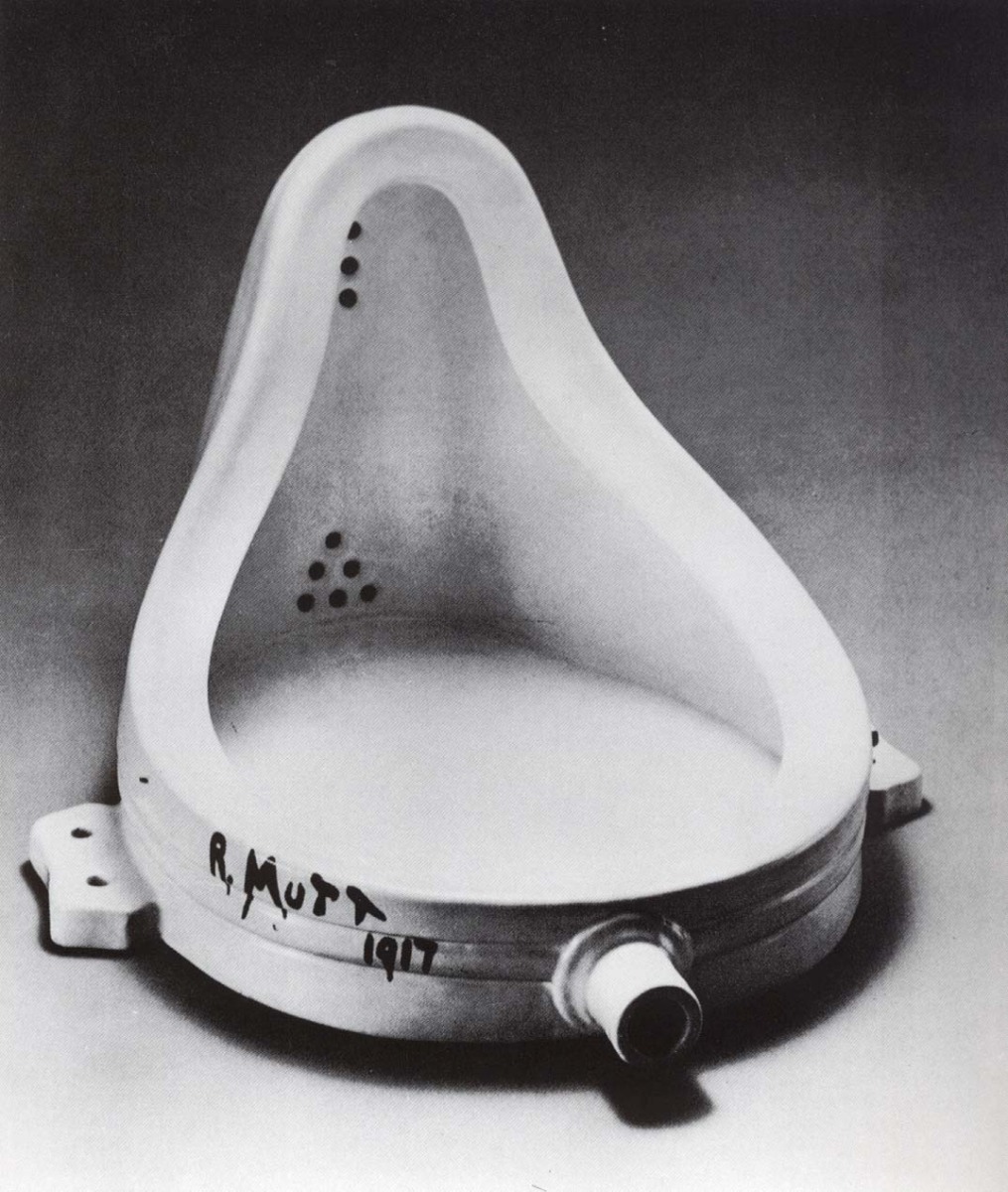

‘Fountain’ by Marcel Duchamp, 1917. Wikimedia Commons

In April 1917, the French-American artist Marcel Duchamp submitted an off-the-shelf urinal titled Fountain and signed ‘R. Mutt 1917’ as his entry for an exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists being held in New York. Even though the Society rules stated that all works would be displayed as long as the artist paid the fee, Fountain wasn’t placed in the show area. Duchamp, a director of the Society, promptly resigned.

The piece, just like the duct-taped banana of today, created quite a stir and divided opinions. But the most passionate, and in retrospect groundbreaking, defence of the work was attributed to an editorial by the artist Beatrice Wood and has been quoted below:

“Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view — created a new thought for that object.”

Fountain, aided in no small terms by this editorial, brought to the fore the idea of ‘readymades’. It questioned what art is, what art should be and pretty much gave birth to the whole movement of ‘conceptual art’. And for that, Marcel Duchamp is rightly considered to be one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

Now back to the banana, and the questions raised.

Anyone can do it, right?

This is one of the first questions that’s thrown up when one encounters a work like Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian. And it happened with Fountain as well.

The reason why this question is raised is because we are generally attuned to looking at art as being primarily an exercise in skill. That’s why we don’t quip ‘I can do it’ or ‘A kid can do it’ when we gaze at Michelangelo’s work on the ceiling of Sistine Chapel or admire a painting by Raja Ravi Verma depicting an event from Ramayana. The skill involved in these works is clearly evident.

‘The Creation of Adam’ by Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel ceiling. Wikimedia Commons

And this brings me to the core reason behind the enduring importance of Duchamp’s Fountain. It marked a paradigm shift where art went from being viewed primarily as an exercise in skill to an exercise in thought.

Duchamp didn’t create the urinal. Just like Cattelan didn’t create the banana. But the thought conveyed by Duchamp shook the foundations of the art world and changed its course forever. Duchamp had developed a disdain for what he called ‘retinal art’ and wanted to create art that served the mind instead of the eye. With Fountain, he opened up a world of possibilities about what could be called art and what it took to become an artist.

Another way in which I like approaching this question is this: Anyone can do it. But the artist knows what she’s doing.

Marcel Duchamp wasn’t a one-off prankster who happened to walk into an art show and place an upside-down down urinal in the midst of other works when no one was looking. Prior to developing his idea of readymades, Duchamp’s work also included paintings that displayed elements of Cubism. And Fountain wasn’t even the first readymade that he came up with. It just happened to be the first one that blew up and registered on a large scale.

The same argument can be extended to the work in question by Maurizio Cattelan. The Italian artist is well-known for his humorous satirical sculptures and has been at it for years. Remember the 18-karat solid gold flush toilet titled America which was in the news recently for its unbelievable heist while on display in the United Kingdom? That’s a Maurizio Cattelan sculpture too!

‘America’ by Maurizio Cattelan. Image by stu_spivack — DSC_0476, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=55387186

What does it even mean?

Now this is a question that is often raised by viewers of works of art. And Comedian is no different. But look closely and you will realise that this question is mostly reserved for works that don’t adhere to certain pre-conceived notions and expectations from a work of art. These include realism, display of skill and conventional ideas of beauty.

But one of the biggest reasons for this, and one that often goes under the radar, is the way in which we end up consuming a work of art. To the uninitiated, being presented with a Jackson Pollock out of the blue is not supposed to make any sense. But unfortunately, that’s how most of us are exposed to works of art — not at curated gallery shows with a lot of context and history on offer but in a newspaper article here and an Instagram update there.

A work of art, like any other creative act, is never born out of vacuum. It’s defined by what came before it and also the material and practical realities of the day. And like any other long-running practice, it’s also defined by the desire of the practitioner to break free from what has been done before and create something new and path-breaking. Examples of this not just abound in visual arts but music, literature and architecture as well.

So the next time you’re faced with a work of art that seems unlike anything you’ve seen before, try and think of it not as an anomaly or aberration but as the latest punchline in a long-running conversation. Once you accept that, embarking on a journey to unravel its context, inspiration and significance will be nothing short of an enriching adventure.

As for Comedian, Emmanuel Perrotin, the gallerist who exhibited it, has called it ‘a symbol of global trade’ among other things, while Cattelan himself has stated ‘ The banana is supposed to be a banana.’ As for me, I think that just like Fountain, it’s a great way to pose the ever-relevant question of what art is, can be and should be.

Marcel Duchamp, while speaking at the Convention of the American Federation of Arts in Houston, Texas, in the year 1957 had said this of creativity:

“All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.”

Enough said. :)

But $120,000 for a 30-cent banana? Seriously?

Now this one makes for a question that can make anyone stop and scratch their heads. But come to think of it, the price of a work of art has never really been determined solely by the market price of the materials involved in creating it. Had that been the case, an oil painting on a standard size canvas would never sell for anything over $100, right?

The price of an artwork depends on a bunch of factors. One of the biggest of these is of course the standing of the artist who created it. Other factors include its provenance, significance, relevance, current demand and so on. According to The New York Times, buyers of Comedian received a limited-edition piece that includes one banana, a certificate of authenticity and instructions on how to replace the fruit (of course).

So do all these factors combined actually justify the price tag? Well, there’s never going to be a definite answer to this one. Personally, I’m not going to lose any sleep over it. I suggest you don’t too.

The real question to think about, though, is: Would so many people still be interested in this work if it hadn’t sold for $120,000?

In conclusion

“Everything that needs to be said has already been said. But since no one was listening, everything must be said again.”

― André Gide

This quote, for me, sums up the relevance of Comedian today. Every work of art worth its salt should provoke a thousand questions rather than offer up simple straightforward answers. And I feel Comedian ticks that box. It raises a lot of questions that Fountain raised more than a century ago. And my sincere hope is that in the age of internet and social media, those questions will travel further and faster than they did in 1917.

More power to the duct-taped banana, I say!

- Shakti Swarup Sahu